Europe’s chances of becoming a net zero continent by 2050 relies primarily on the success of its carbon trading market.

The 2015 Paris agreement set out a new legislative framework to get Europe to net zero. The expansion of the carbon trading market was the most important step amongst those policy decisions. The EU commission describes the market as the ‘cornerstone’ of the bloc’s action against climate change. However, critics suggest the market has serious flaws, pointing to the collapse of the first international carbon market set up in 1997.

We ask if it is possible to achieve rapid and substantial reductions of emissions through this new generation of carbon markets.

How does the carbon market work?

The carbon market is a financial mechanism which effectively places a price on carbon pollution. The market, therefore, has established an incentive for all corporations to reduce their emissions because high carbon output will incur a financial penalty.

The regulatory carbon market works on the basis of ‘cap and trade’. Within the EU market, the EU sets a cap or limit on carbon production across each sector. Most carbon-intensive industries that operate in the bloc are subject to this cap, including power stations, steelworks and civil aviation. Estimates suggest that the activity of these companies accounts for approximately 40 percent of the EU states overall emissions.

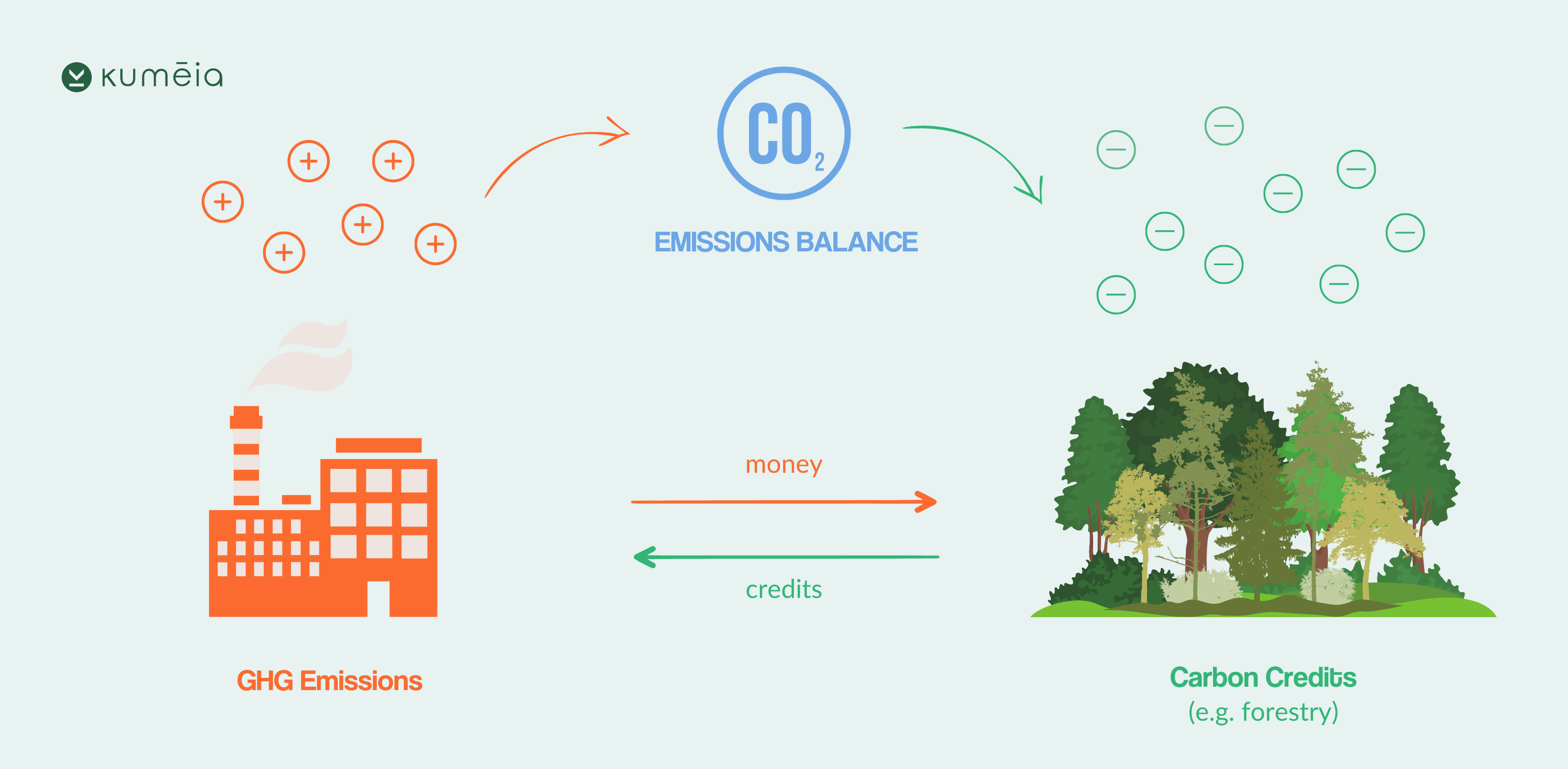

Companies receive their cap in the form of carbon credits. Each credit equates to one metric ton of carbon and the total amount of credits represents the total amount of carbon the company is ‘allowed’ to produce. In simple terms, a carbon credit is similar to a permit which confers the right to create carbon.

After the regulators set the cap, the trading of carbon credits can begin. If a company reports carbon emissions below their cap, they are in a position to sell their surplus carbon credits. Companies who failed to meet their cap have an obligation to buy credits, thereby, increasing the limit on their carbon production. So, the carbon market encourages emitters to pursue greater energy efficiency through the trading of credits.

Carbon offsets and the voluntary market

The cap and trade system is only one side of the carbon market. There is a secondary, purely voluntary, market which directly funds projects aimed at reducing GHG emissions. Many of these offset projects take place in developing nations, meaning this type of carbon trading facilitates the movement of financial capital from the world’s biggest economies to smaller markets. Offset projects include renewable energy schemes and carbon sequestration in soils and woodlands.

Investors can purchase offsets, in the form of carbon credits equalling one metric ton of CO2 or CO2e, to counterbalance their environmentally damaging activities. For example, the owner of a private jet might seek to buy carbon offset credits because their air travel significantly increases their carbon footprint.

Corporations will likely have similar motivations under what is called corporate social responsibility (CSR). This social responsibility in a practical sense means that firms will engage with projects, like tree planning schemes, which do not directly advance their economic goals.

There are a number of different types of carbon offset initiatives which companies can invest in. However, the most popular investments tend to be reforestation and renewable energy projects.

For many companies carbon offsetting is an important part of their strategy to reach carbon neutrality. However, there is an understanding that offsets alone cannot support their transition to net zero. Offsets should be a small proportion of companies’ investment plans; their main focus has to be lowering their emissions within the regulatory framework of the cap and trade market.

Can the carbon markets deliver net zero?

There has been much criticism about the robustness of the carbon credit market and the legitimacy of carbon offsetting.

The EU frames their carbon market or Emissions Trading System (ETS) as a clear success story. Researchers handling EU data from between 2008-2016 suggest that the ETS, which then regulated around half of the EU’s emissions, saved more than one billion tons of carbon (Bayer & Akiln, 2020). This was achieved when the price for carbon was relatively low. Since then, the EU has sought to strengthen its carbon market.

The governing body announced measures, along with new climate change targets (minus 55 percent emissions), to increase the price of carbon. For example, lawmakers decided to phase out free allowances known to suppress prices and brought new sectors (road and maritime transport) into the market. Free allowances, given out to uphold market competition rules, are basically a subsidy for heavy polluters.

These new measures did cause a spike in carbon prices. In early 2022, the price of a carbon credit was nearly 100 euros. However, since the onset of the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis, the price has fallen. Despite the conflict, the EU hasn’t, as of yet, delayed or cancelled any of the reforms.

How reliable are the claims about carbon offsets?

Observers fear that polluting companies buying up carbon offsets are simply indulging in ‘greenwashing’.犀利士 Greenwashing is a term used to describe activities in the green sector which lack substance and only serve to protect a company’s image. For example, several major oil companies are investing in planting more trees, this notionally feels like a sustainable idea, however, in reality, many forestry projects have a negligible impact on carbon pollution.

Tree planting projects are becoming big business in the offset market, but their success is far from guaranteed. Various schemes in the past have failed due to a lack of understanding about local ecosystems and soil types. Researchers from Colorado State university conducted studies in afforested regions of northern China (Hong, S., Yin, G., Piao, S. et al, 2020). They discovered that the carbon capture potential of newly forested areas is often overestimated.

Delegates at the COP26 summit in Glasgow echoed the concerns about the offset market and greenwashing. The UN Special Envoy for Climate Change and Finance, Mark Carney, said the current state of the market was a problem, highlighting the lack of standardisation and transparency as key issues to address.

It is clear that the offset market has flaws and shouldn’t be the primary tool we use to lower our emissions. However, the principle behind the voluntary market is sound, carbon offsets have a part to play in our green transformation. Crucially, the market channels funding to projects that in time will be significant and potentially game changing. This isn’t only tree planting schemes, offset capital helps green entrepreneurs trial and develop new green technology and machinery.

Follow our climate change blog to receive more information about projects in your region and how governments are financing the fight against carbon emissions.

Check out these resources to further your understanding of carbon credits and carbon offsetting:

- https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en

- https://www.cleanenergywire.org/

- https://carboncredits.com/