Tree planting projects and restoration of our damaged forests won’t deliver net zero carbon emissions. However, forestation, if done right, can enrich our lives and communities in a number of ways.

Forests perform an incredible role supporting life on earth because their survival relies primarily on the most potent greenhouse gas – carbon dioxide.

Through the process of photosynthesis, trees will absorb and convert CO2 (alongside water and light energy) into sugars for sustenance and growth. Over the span of a single year, a healthy tree can remove as much as 48 pounds of carbon from our atmosphere (USDA, 2019).

In short, forests act as a natural ‘factory’ for clean air. However, despite this remarkable ability, we should not assume that creating new forests is a cure-all approach to the climate crisis.

Forestation is a more complex task than simply planting and protecting trees. Even if it was that straightforward, the planet does not have enough space for new forests to absorb all the carbon emissions we produce.

The common failures of forestation projects

Building a climate-resilient forest or woodland requires specialist knowledge about soil properties, weather patterns and native flora and fauna. Sadly, far too many projects have proceeded without a clear understanding of these facts.

Choosing the wrong location

Due to the lack of suitable locations, a number of forestation projects have chosen plots of land where trees do not typically grow. This is a problem because the introduction of a new plant species can upset the balance of an ecosystem – ecosystems, not newly planted forests, absorb and store carbon.

Researchers (Parr, C.L., Gray, E.F. & Bond, W.J., 2012), observing the grasslands of southern Africa, recorded many changes to natural life in areas where open savanna had grown into dense thicket. For example, certain predators enjoyed greater hunting success because the increase in vegetation helped them stalk prey more effectively.

Iconic animals of the African savanna such as zebra and bison will suffer if thickets continue to encroach on grasslands, as predators gain an unfair advantage.

Aside from destabilising ecosystems, choosing the wrong location for a forest could put more carbon back into the atmosphere. One project in the Lake District in England, permanently damaged an area of peatland that was an important carbon sink. Peat bogs (marshes) store carbon, therefore should not be used for planting new forests.

The team involved in the project had misidentified the soil and had already begun digging drainage ditches before they realised their mistake. The disruption to the peat soil caused the area to dry out and release the carbon it had stored. The UK Forestry Commission, who funded the scheme, said they needed to work more closely with ecologists when analysing soil samples (BBC, 2020).

Planting the wrong tree

After selecting the location, the next important decision is choosing the right tree.

The best choice of tree is one that is native to the area and therefore likely to harmonise with the soil and local wildlife. Non-native trees are a more risky proposition because they might fail to adapt or alternatively they might dominate their surrounding environment as an invasive force.

In the US, the Fish and Wildlife Service suggested that around half of the country’s endangered native trees have declined due to the presence of non-native species. The service advised urban planners and landscape architects to avoid the practice of using more aesthetically pleasing exotic trees, like Cherry Blossoms, for fears that they might establish themselves beyond their intended range.

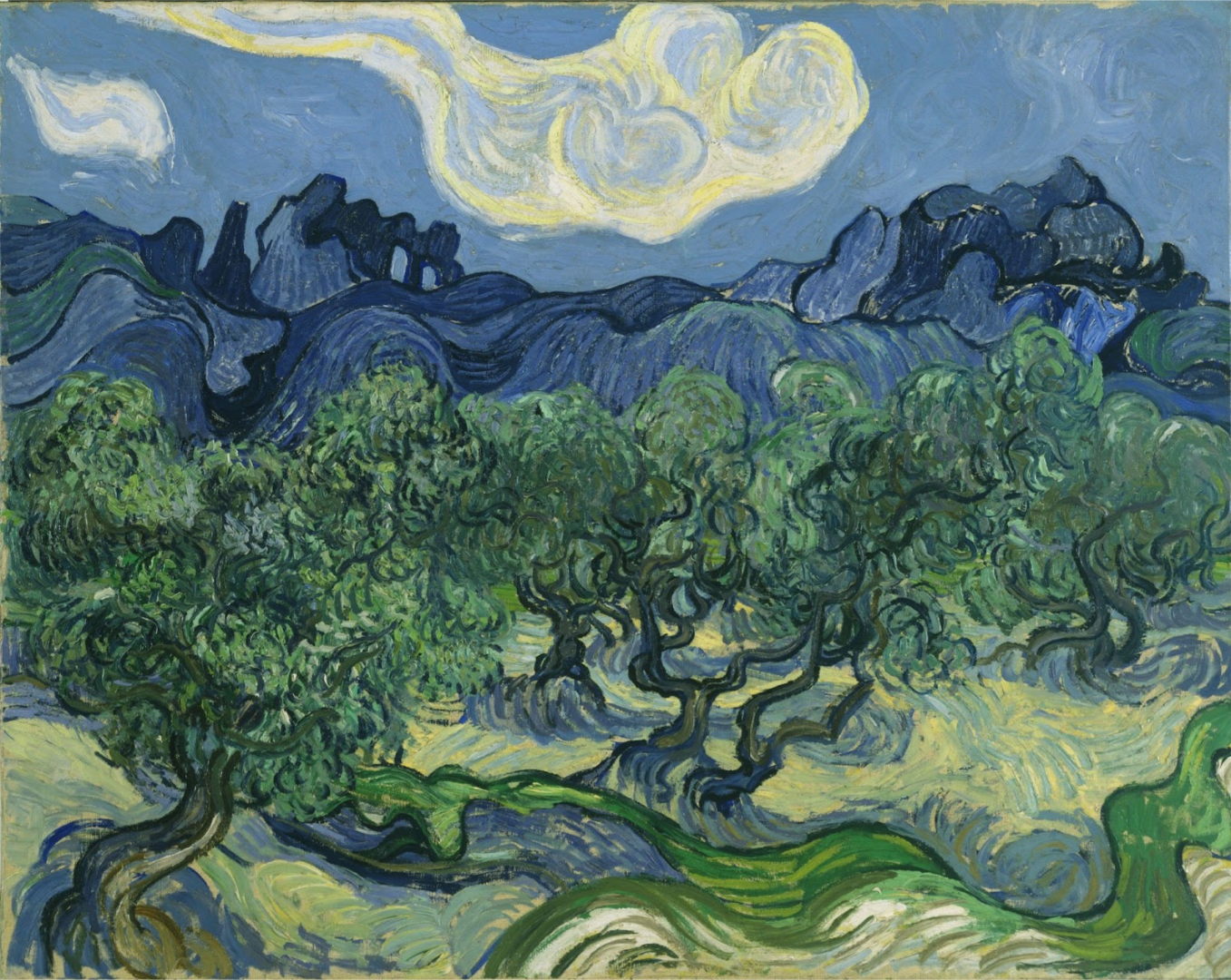

Another problem that plagues forestation projects is focusing on only one type of tree. If you look at pictures of some newly planted forests, you will likely see hundreds of rows of the same variety of tree. This is called a monoculture plantation.

In terms of carbon sequestration, monocultures are far inferior to diverse forests. A study conducted in northern China proved that species richness increased carbon capture. The paper (X. Liu. et.al, 2018) recommended that afforestation projects should create multi-species plantations to absorb more CO2 from the air.

Interfering with nature

Often the best solution for building a resilient forest is to let nature run its course.

Many ecologists have come to the realisation that forests should be left alone without any human interference. In this case, forestation involves zero planting activity, teams simply place fences around a plot of land to prevent animals from grazing and let the trees grow naturally.

This method of forestation is much more cost-effective than other strategies and it eliminates the possibility of failure. However, some people resist the idea because natural regeneration takes time and this makes it difficult to set clear targets.

Tree planting and the carbon markets

Tree planting is a popular way for organisations to offset their carbon production. However the carbon markets, which facilitate investment in the maintenance and expansion of forested land, suffer from lax regulation.

Bloomberg’s investigation (Bloomberg Green, 2020) into the US carbon market reveals some questionable activity involving forestation companies and their recruitment of small landowners.

In one particular case the environmental group, Nature Conservancy, sold carbon credits to preserve forested areas which did not need protecting. Agents from the group would approach landowners, who had no desire or intention to cut down their trees, and sign them up to their carbon credit scheme. The credits issued for this land, some of which were bought by large corporations like Disney, did not directly fund any new tree planting activity nor did it protect existing trees from deforestation.

The sale of these ‘empty’ carbon credits is detrimental for the carbon offset market as a whole. With the growing perception that forestry carbon credits have little value, investors will exit the market. This is a significant problem because we need the price of carbon credits to be much higher to reach our emission targets.

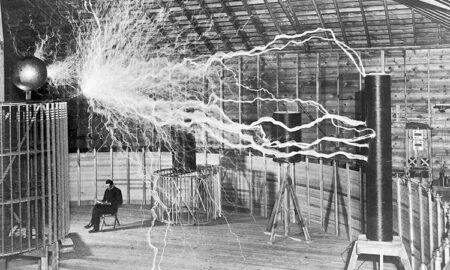

United Airlines, which purchased credits with another company engaged in dubious forestation schemes, is one of the firms pulling its investment from the offset market. They are instead financing a tech firm looking for a non-natural way to absorb carbon from the air.

Clearly, reform is necessary to bring back trust in the forestation and the carbon offset business.

Promising future with community-led forestation

Amongst the failures and missteps, there have been many successes in the forestation sector.

One key theme of the successful projects is that local people play an important part. We must make sure native people have an economically viable future in their forest home and that projects focus on education and skills to cut out costly errors.

The Green Belt Movement, Urban Greening Project

On the Kumēia science blog, we have already mentioned the work of the Green Belt Movement in Kenya. We championed the career of its pioneering founder Wangari Maatthai, who passed away in 2011.

Thankfully her legacy lives on, and the movement continues its mission to support women to plant trees and educate children. In an event celebrating the 10th anniversary of Maathai’s passing, the new Urban Greening project was announced.

The Urban Greening project is a perfect example of a forestation scheme with sound guiding principles. The organisation has been careful to select only indigenous and high-value fruit trees. The use of native trees ensures the new forest won’t negatively upset the current balance of the ecosystem. And the fruit trees give the local community a source of income, as they can sell the surplus fruit for profit.

Forestation is not a cure all approach for our climate crisis. However, if we can build diverse forests which promote the economic interests of the local people, we can reduce a significant amount of our carbon emissions.

To learn more about forestation and good tree planting practice, explore these resources:

- https://www.caryinstitute.org/news-insights/feature/rethinking-forest-carbon-offsets

- https://rewildingeurope.com/what-is-rewilding-2/